Posted on Posted on By Palmer Hasty

Brooklyn native Fred Mannarino delivered the Brooklyn Eagle in the 1940s…

By Palmer Hasty

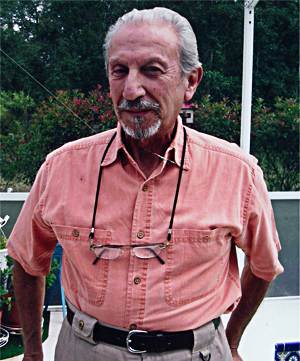

Artist and Brooklyn native Fred Mannarino lives in the house he had built 29 years ago in Spring Hill, Florida. Mannarino is 87 years old and remembers a stunning amount of details from his Williamsburg, Brooklyn childhood during the 1930s until the 50s, yet, as he pointed out with a laugh; “Although I can remember when I delivered the Brooklyn Eagle in the 1940s when it cost just a nickel, but hell, I’m getting so old now I can’t remember what I was doing an hour ago.”

His father, Joseph Mannarino, was an immigrant from Calabria, Italy, who came directly to Brooklyn when he was 13 years old. In Calabria, when he was very young Mannarino’s father earned money transporting bricks for the brick layers at local construction sites. In Brooklyn during his teens he worked in German restaurants as a potato peeler making $37 a week, which was where he learned how to cook.

Mannarino’s mother, Catherine, was also from the Calabria region of Southern Italy. She came to Brooklyn when she was just one year old. She was a seamstress and made a lot more money than his father. During the second World War she made lapels for the Army’s jackets and winter overcoats. Mannarino said his mother was also addicted to gambling and beautiful jewelry, and that she regularly played the “numbers”, also known as the “Italian Lottery”.

It was from her gambling profits that she was able to purchase the family’s popular neighborhood diner on Flushing Avenue for $900.

The interview was conducted on Mannarino’s open back porch that was part of the poolside sitting area for a screened-in swimming pool. While drinking some very good, strong Italian coffee, I asked Mannarino about his job delivering the Brooklyn Daily Eagle in Williamsburg when he was a kid.

FM: “I was 11 or 12 when I delivered the Eagle. I don’t remember how I got the job, but we used to meet the guy who brought the papers to a certain a empty store front. The papers were brought there early in the morning. After school we would go pick up the papers and do our routes. I had maybe 40 or 50 people I had to deliver to.

All my deliveries were to tenement houses. If the ground floor family wasn’t at home it was difficult to get to the other apartments to leave the paper. And on Sundays I didn’t like to ring the bell so early so I made an agreement that I would just leave the papers in the foyer where they had the mailboxes.”

BE: How did you deliver the Eagle?

FM: “They gave us a leather bag that we strapped around our shoulders with a big pouch on the side. In the winter time it was difficult so my father would help me. On the weekends we had to wake up at 5 AM. The snow would be about a foot deep. On Sunday the papers were about double the normal size so we’d put them in my father’s old 33 Chevrolet and I would take out a bagful at a time and walk up the street…I’d tell my father: I’ll meet you on the corner of Bleeker or Troutman Streets.”

BE: You never used a bike?

FM: “Yes, I was about to tell you that.I decided I wanted to let my father relax on the weekends, especially during the Winter months. So he found someone who wanted to sell a bike. We called bikes two-wheelers back then. It had a basket on the front to hold the papers. That still created another problem because the basket would hold only so many papers, so I had to do a lot of back and forth to refill the basket.”

BE: How much did you earn?

FM: “Nothing, nobody got paid. We just relied on tips. Back then no one seemed to have a lot of money so the tips were small, like nickels and dimes. Sometimes instead of money they even gave us food, like an apple or something. I delivered the Eagle for about three years and eventually stopped and found a new job delivering the Saturday Evening Post, that magazine with the Normal Rockwell covers. That was easier to deliver but a harder job because I had to go out and solicit the customers, and I only got about 15 people.

BE: Was there competition from other papers in the early 1940s?

FM: “The Eagle was absolutely one of the most popular papers in Brooklyn at that time. There were three other papers that were popular; The Daily Mirror, The Daily News, and The Journal American. The other papers costs 3 cents and the Eagle cost a nickel. They all had great comics, the classics; Prince Valiant, Tarzan, Popeye, Dagwood, Little Orphan Annie and Dick Tracy.

I remember the opposing paper right next to my route was the Long Island Daily Press. We picked up the papers in the same place. That paper catered more to the Queens area, west of Bushwick Avenue. I can remember sometimes I would be on one side of the street delivering the Eagle and he would be on the other side delivering the Long Island Daily Press.

BE: Did you play any stickball as a kid?

FM: “Yes I did. We played stickball with a broom handle. We played on Vandervoort Place, where PS 88 used to be. It was a one way street for one block that went north off Flushing Avenue and intersected with Thames Street.

BE: A one-way street would be great for stickball wouldn’t it?

FM: “Yes it was, because of course there was less traffic on a one-way street. But the problem was, we broke so many windows. The street was narrow and back then the houses were built where three large windows came out and around, like a bay window. We’d break a window and everybody would scatter.”

“When I went home I’d tell my father I broke another window…he’d get upset for a minute but he always went over and paid the neighbor 50 cents so they could replace their window…when someone else broke a window his family would also do the same…we always replaced the windows…everybody knew everybody, we were all very close.” Note: Today Vandervoort Place is primarily a fenced in parking lot on one side and various brick walls on the other side with murals of graffiti.“

BE: What was Williamsburg like back then?

FM: “Williamsburg, and especially Flushing Avenue, was primarily an Italian neighborhood with quite a few Jewish people. Everything was different back then. Gabalino’s was one of the big grocery stores. At that time you could build up a bill. You went there and bought something and the owner would keep your name and what you spent, and at the end of the week when you got paid you would go and take care of part of your bill, or pay it all off. I remember he sold milk and beer in big barrels and you brought your own containers. Times were still hard through the 1930s after the great depression. My parents and most of our neighbors were so poor at that time.”

“I remember our source of fresh bread at that time was not exactly a store. They had a big oven beneath the ground where these Italian couples would bake bread. As kids we recognized where it was because when it snowed their sidewalk was always clean when everybody else’s was covered with snow. The warmth from the ovens melted the snow on the sidewalk. They called it Rizutto’s Bread and that’s where we got our fresh bread. They didn’t have real store, they sold bread out of the cellar and distributed to a lot of other stores around Williamsburg and Brooklyn.”

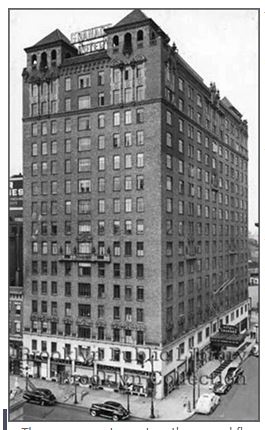

BE: So you got married in the old Granada Hotel?

FM: ” Yes. My wife and I started dating in 1954 after I returned from the service. Her name was Catherine Fischer. When we were kids she had lived just two doors from me but I didn’t meet her until I returned from the Navy. We lived at 1063 Flushing Avenue and her family lived at 1067.”

“We got married at the Hotel Granada. If I’m not mistaken I remember it was right in the heart of the Fulton Street area. We had 365 guests for dinner at the reception, a 6-piece orchestra, and we had to pay the band for an extra two hours because nobody wanted to go home.”

“I remember one night Cathy and I went out to the Brooklyn Paramount, which was on Flatbush Avenue. I remember this one particular night when we went there and when we came out of the theater all the cars were jammed onto Flatbush Avenue. And Fulton Street was completely full of cars honking and the people were dancing on the roofs of their cars because the war had ended in Germany. It took us about 2 or 3 hours to get away from the scene. When we got home my future mother-in-law was hanging out the window waiting on us, and we had to explain to Cathy’s parents why we were so late.”

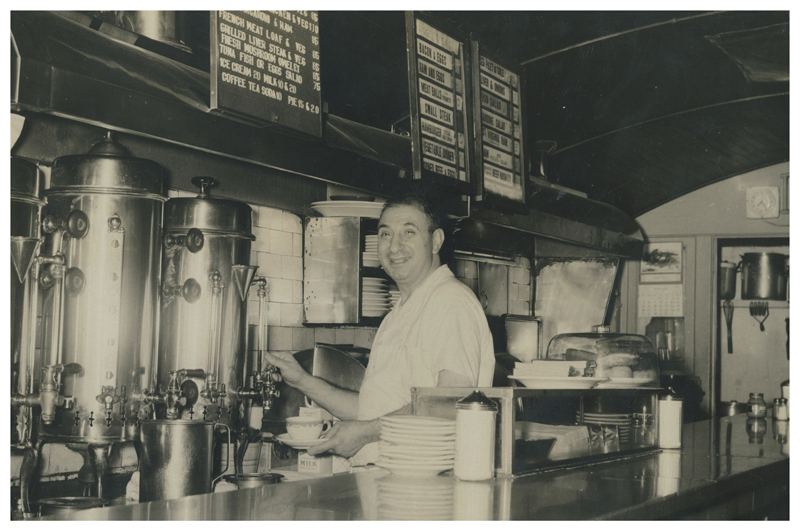

BE: What can you tell us about the family diner?

FM: “Just before the war my father bought a diner on Flushing Avenue. It was a small diner on the side of a gas station. It was also what they called a lunch wagon, like a trolley car with 17 stools and just five 2-person tables.”

“One of my mother’s brothers nicknamed ‘Silky’ was a bookie. He knew everything that was going on in the neighborhood. He found out about the diner from a guy he played the horses with. Silky told my father; ‘There’s a diner over there for sale and he only wants $900’.”

“My mother played the numbers, and when she won, she won big! So my parents were able to buy the diner and fix it all up. It was a family run operation. My mother was the cashier, my father the cook, my aunt Rose, my mother’s sister, was a waitress and her brother Johnny was a counter man.”

“It was just before the war, I remember we still had to use stamps to buy sugar. People were always stealing sugar so my father had to remove the sugar jars from the tables. We had excellent clientele, everybody came to the diner, it was great.”