The Genius and Generosity of Donald Roebling (with a touch of eccentricity)

Compiled, Edited, and Written by Palmer Hasty

Part 1: The Roeblings

Donald Roebling’s great grandfather, John A. Roebling, is well known around the world, and especially in Brooklyn, because of course, he designed the historic Brooklyn Bridge. Later members of the Roebling family also left some very unique and unforgettable footprints in Florida during the 1920s and 1930s. And although the history of the Roebling family’s connection to Brooklyn, especially Brooklyn Heights, is familiar historical territory, nevertheless, we will quickly recount some those highlights leading up to John A Roebling II, and his son Donald Roebling’s important contributions in Florida.

The Brooklyn Bridge designer John A. Roebling died in 1869 from complications (tetanus, lockjaw, and seizures) related to his toes being amputated after his foot was crushed by a ferry boat while he was standing on the edge of a dock researching the right location for the Brooklyn Bridge.

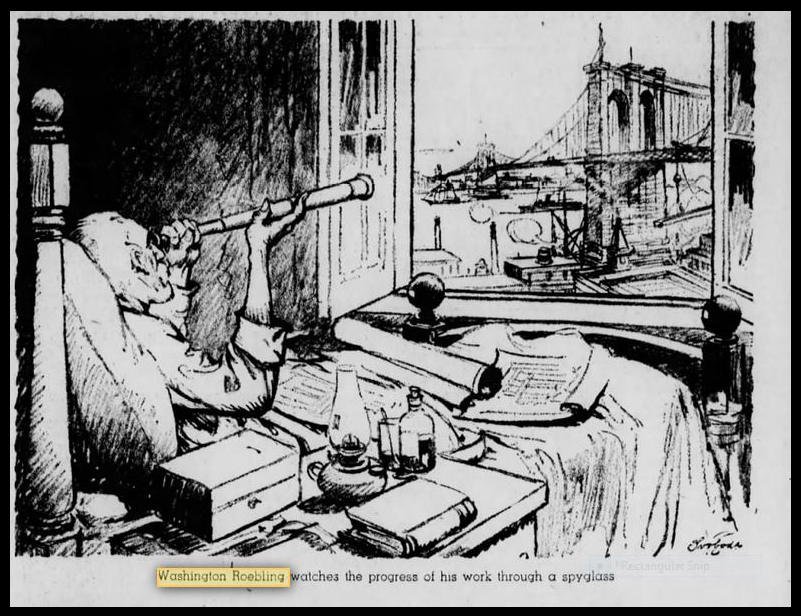

John A. Roebling’s son, Washington Roebling, along with his wife Emily Warren Roebling, continued his father’s work on the great Bridge while orchestrating the construction from an apartment in Brooklyn Heights.

Washington Roebling (Donald Roebling’s grandfather) became chief engineer for the bridge project after his father’s death. According to the renowned biographer David McCullough, in his book The Great Bridge, in 1870 a fire broke out inside one of the gigantic caissons under the river. The caissons are the underwater foundations for the two famous stone towers, along with the suspension cables, that have identified the iconic Brooklyn Bridge for more than a century.

Washington Roebling himself directed the efforts to extinguish the fires within the caisson, and as a result, contracted decompression sickness, which eventually wrecked his health and left him unable to visit the site.

The next phase of this particular Roebling story is popular lore in Brooklyn Heights, where Roebling had an apartment, and from where he had a good view of the construction scene. He directed the completion of the bridge construction from the apartment window on Columbia Heights. Roebling’s wife Emily studied bridge construction and took over assistant engineering duties, becoming his liaison and carrying his instructions from the apartment to the crews on site.

These three images are from two articles about Washington Roebling originally published in the Brooklyn Daily Eagle. From the left, images 1 & 2 are about his health in 1887, four years after the completion of the Bridge, and the third article (far right) is from a 1917 Eagle wherein Roebling reveals to the reporter that someone warned him there were rumors the Bridge was going the fall down.

As the samples of original newspaper articles (above) from a late 19th century and early 20th century Brooklyn Daily Eagle reveal, the paper liked to periocidally report on the progress of Roebling’s health following the completion of the Great Bridge, as well as general human interest news, since the Roebling family and Brooklyn history are indelibly linked.

As we will retrace below, Washington Roebling’s grandson Donald Roebling, under completely different circumstances, while living a life of luxury and eccentricity in Clearwater, Florida, would nevertheless display the Roebling engineering genius, determination, and resourcefulness.

John A. Roebling II, the only child of Washington and Emily Roebling, was Donald Roebling’s father. After the first World War, around 1920, John A. Roebling II became a nationally known financier, entrepreneur and philanthropist, while managing from their estate in New Jersey, the Roebling family’s immense fortune.

John Roebling II’s wife Margaret contracted tuberculosis, and with his wife’s health in mind, in the 1920s he started building a winter estate in Lake Placid, Florida, about 35 miles slightly northwest of Lake Okeechobee. It was also during the late 1920s that Donald Roebling moved to Clearwater, Florida.

Part 2: John A. Roebling II and His Son Donald

Donald Roebling was born in New York City in 1908. He grew up in the family’s mansion in New Jersey. Roebling was an overweight youth and grew up to be a very large man. At 6′ 3″ he eventually weighed between 350 and 400 pounds, in part due to his addiction to sweets.

In his youth Roebling also showed what many considered to be signs of both his genius, and his eccentricity. Even though he didn’t excel academically in school, his mind was naturally capable of grasping and solving complex problems quickly. (Later, his secretary in Clearwater, Florida, would describe Roebling as having a mind like a “steel trap” along with a “great sense of humor.” )[9]

Against his family’s wishes, he refused to enter an Ivy League college. Instead he attended the Bliss Electrical Academy in Washington, DC. In his book Roebling’s Amphibian, USMC Major Richard Roan described the young Roebling as “strong-willed, temperamental and overweight.”[1] In 1928 he was “asked” to leave the Bliss Academy because of differences with the his instructors. Soon after leaving Bliss Academy the young Roebling went to Clearwater, Florida, to live with his cousin Margaret MacIlrane. He apparently liked Clearwater and decided to stay.

In 1930, when he was just 21, he inherited $5 million from the family fortune and started his own construction company, specializing in building luxury homes.[1] He also purchased at that time seven acres of beachfront property in the Harbor Oaks section of Clearwater, and proceeded to build a 15-room brick Tudor style mansion with a giant swimming pool surrounded by extensive gardens. He named the estate at 700 Orange Street after his first wife, Spottiswoode. At the time it was said that for many years the “fortress” like structure was the largest and best built single family dwelling on the West Coast of Florida.[1]

In December of 1979, twenty years after Roebling’s death, his Harbor Oaks estate was placed on the U.S. National Registry of Historic Places. The estate and the mansion are still there today.

Built in 1930, the Roebling Mansion today.

Part 3: John A. Roebling’s Lake Placid Estate and the great Hurricane of 1928

Meanwhile, in 1928, the Lake Okeechobee Hurricane hit the east coast of Florida north of Miami and caused massive destruction with winds up to 150 mph. The hurricane came ashore at Palm Beach where the residents were as prepared as they could be, while residents further inland were tragically unprepared.

The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) rated this hurricane as the 2nd deadliest hurricane in American history. The area that suffered the most devastation was the south side shores of Lake Okeechobee. The hurricane created a 10-foot surge from the lake and washed over 8-foot dikes, then flooded a 75-mile area.

(You can view pictures of the devastation at this link: http://www.srh.noaa.gov/mfl/?n=okeechobee.[8]

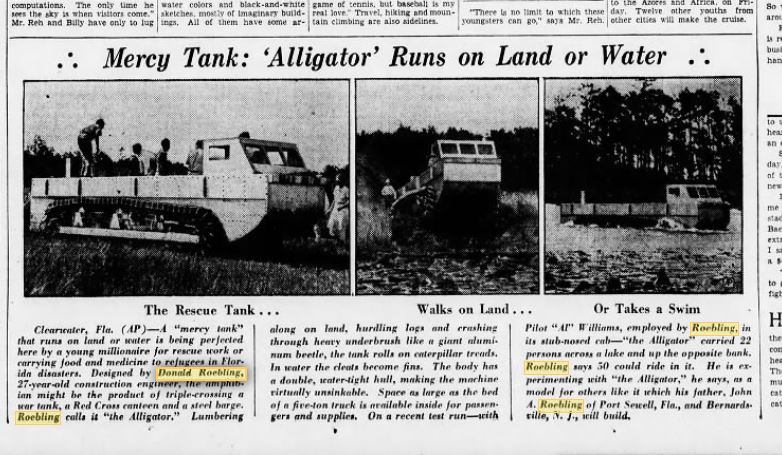

To give you a glimpse into what caused John Roebling II to come up with the idea of creating the now famous Donald Roebling “Alligator”, I quote from a 1988 article in a south Florida newspaper, the Sun Sentinel (written by Liz Doup).[10]

Liz Doup recounts via interviews with lucky survivors, some of the devastation caused by the monster hurricane.

Forty miles west of the coast, rain filled Lake Okeechobee to the brim and the dikes crumbled. Water rushed onto the swampy farmland, and homes and people were swept away. Almost 2,000 people perished.

At McCormick’s home, someone cut an escape hatch in the roof. The piano was moved under the hole and up they climbed to escape the rising water. The house, knocked off its foundation and moving with the raging flood, twisted and turned while McCormick hung on for her life.

‘I was holding on to the roof and calling out to my mother.’

Her family, like most of the casualties, probably drowned in the deluge.

From the Aftermath…

But something had to be done with all those bodies. And it had to be done quickly.

“Bodies were stacked like cordwood.”

Days later, a much bigger grave for more than 1,000 victims was dug…”

In the end, that wasn’t good enough or fast enough.

“After about the fifth day, we couldn’t handle it, not with the heat and humidity. You couldn’t identify them, and we had to burn them.”[11]

With his Florida estate in Lake Placid not far from the devastated area, according to records and Major Roan, John Roebling II witnessed some of the devastation first hand, and became personally interested in the disaster. He sent a group of his own employees to help with rescue efforts in some of the towns surrounding Lake Okeechobee. On request, his employees reported back to him that many of the lives lost during the aftermath of the hurricane was a result of rescuers not being able to reach the victims in time, having to traverse miles of flood and muck. There was simply no way to physically get to many of the stranded victims.[1]

In his book Roan describes what happened then; “One of the men suggested to Roebling that a vehicle, or boat, that could travel on land and through mud, as well as negotiating deep water, would have helped immeasurably. They all agreed that hundreds of lives could have been saved if only the rescuers had been given the means to reach the victims in time.”

Roebling decided that the kind of amphibious vehicle he and his employees had in mind would be a good challenge, and a worthy project for his wealthy son in Clearwater, that is, to design and build a rescue vehicle that could traverse both land and water.

Little did anyone know at the time that, as Major Roan pointed out, the young eccentric millionaire in Clearwater would spend the next eight years building and testing, initially for the purpose of rescuing future hurricane victims, an invaluable amphibious assault landing craft for the U.S. military that would be a major factor in winning the Pacific front during World War II.[1]

Part 4. The Eccentric Millionaire is Challenged by His Father: “Apparently to him, the problem was simply the wrong side of the solution.

The design, building, and testing of the different models for Roebling’s amphibious vehicle is a fascinating feature story unto itself. Here I will make note of just the highlights, or as my title suggests, present some footprints that led to Roebling developing his now famous amphibious vehicle, as chronicled by Major Roan.

Donald Roebling not only inherited a fortune of $5 million (in 1930 $5 million had the buying power of $1.25 billion today). He apparently also inherited some of the renowned Roebling engineering genius. But up to that point he was primarily considered a young, wealthy eccentric who just tinkered around. He had a machine shop built on his new estate in Clearwater so he could build things.

At his father’s request, and with his father’s financial support, he began the project he imagined would be used to rescue future hurricane victims in Florida.

In his book Major Roan never hesitated to point out several times how incongruous it was for someone living Roebling’s lifestyle, so far removed from a military mindset, to have solved a problem the Marine Corps had already been trying to solve for years.[1]

Underneath the eccentric personality was an exceptionally creative mind with a natural instinct for solving complex issues. Roebling appeared to have the kind of mind, or instinct, that did not burden itself with the questions that accompany the time consuming process of deductive reasoning; apparently to him, a problem was simply the wrong side of the solution.

All during the eight years of designing and building the four different amphibian models Roebling and his small staff, driven more by creativity than methodology, very rarely kept notes or blueprints.[1]

In what appears to be an example of the young Roebling’s determination, and by some accounts, his eccentricity, during the early phases of development Roebling actually did the preliminary testing of the vehicle within the confines of his own estate, that is, on his driveway and in his large swimming pool.

Part 5. Roebling starts production of the “Alligator”

Photo:The Spirit of Morton Plant: A Retrospective 1919-1991.

Building the amphibious vehicle was an arduous task, as mentioned above, that took eight years.

Roebling hired three assistants (his technical staff) and by January 1933, production was in full swing. The vehicle needed to be able to float in water, and be sturdy enough to maneuver on rugged terrain.

In the 1930s aluminum was a new, lighter weight material and also strong enough for land use. Roebling decided that aluminum would be best for keeping the vehicle light enough to float, yet it also turned out that aluminum was too soft for the metalworking tools in his shop. Roebling figured out that woodworking machinery was better suited for working with the softer metal.[1]

Production on the first prototype went as quickly as possible because Roebling had wanted to have it ready for the 1933 hurricane season in Florida. Nevertheless, this was ambitious and unrealistic, and turned out to be wishful thinking. It was a goal he could not possibly reach.

His first prototype was finished in 1935. That is when the nickname “Alligator” was first attached to the vehicle. It was 24 feet long and weighed 14,350 pounds. It was powered by a 92 horsepower Chrysler engine. The first model was somewhat of a monster, and although it “worked”, there were problems with the tracking cleats when it maneuvered over uneven landscapes.

As Major Roan described it; figuring out the propulsion system was the result of “a truly revolutionary imagination.”[1]

Roebling figured the problem was related to having two different propulsion systems. Major Roan said that previous attempts by the Navy involved trying to coordinate two different, or separate propulsion systems, one for the land and one for the water.

Roebling thought one propulsion system for both elements was the key, and he was right. It was based on a paddle wheel track system, like a paddle wheel boat operates in water. Roebling’s concept would have the cleats work like the paddles of a paddle wheel boat in water, fixed to a moveable track.[1]

Although Roebling was on the right track, so to speak, as Major Roan explained, “The 1935 prototype was heavy as well as flimsy and broke apart on rough terrain…and the straight paddle-wheel cleats set straight across the track, were inefficient in the water, going only 2.3 mph.”

Roebling tried to sell this version of the vehicle to the Red Cross and the United States Coast Guard, but no one was interested.

Part 6. Although “it worked”…It Was Back to the Drawing Board

Photo: The National Archives.

as published in the Brooklyn Daily Eagle.

Roebling would not accept defeat. He stripped the vehicle down and started over on the second version.

The second model was completed in 1936 and although version two was lighter and faster, the tracking problems remained unsolved.

The third model showed improvements but somehow got hung up when trying to reach higher terrain. The main problem with the tracking system persisted. He would have to invent a new tracking system if his “Alligator” was going to be reliable as a hurricane rescue vehicle.

Finally in 1937, with the fourth model, the amphibious vehicle was close to being a viable machine for its purpose.

Roebling had installed roller bearings that were built into the chain track instead of bogie wheels. And fixed-idler-blocks replaced the idler-wheels, which made for a lighter, smoother, and more durable performance on embankments. He also replaced the straight paddle-wheel cleats with curved cleats than enhanced the water speed. As Major Roan noted, “It was the diagonally affixed curved cleat and paddle wheel principle that produced the Alligator’s only patent. (Patent No. 2138207, that Roebling would later sell to the military during the height of WWII for only $1 without fees.)

This new version of the Alligator weighed 5,650 less than the first version from 1935. The water speed was 8.6 mph and land speed was 18 mph. Roebling, and his father, thought the new model had real commercial potential.

Part 7. The local press and Life Magazine

There was some local fanfare and media coverage following the completion of the fourth model in 1937. Roebling was testing the new vehicle in St. Joseph’s Sound in Clearwater Bay as well as lakes and swamp areas around Clearwater and Dunedin, a small town just north of Clearwater.

All the local press he attracted caught the attention of Life Magazine. Life Magazine sent writers and photographers to Clearwater to see what it was all about. All the press coverage culminated in a 2-page feature story in the October 4, 1937 issue of Life Magazine.

The Life article praised the Alligator. “The Alligator’s amphibious qualities…its ability to crash through mangrove swamps grinding whole trees and shrubs to matchwood…with a 40-man capacity and impressive speeds…all with a $10,000 production price.”

The Life Magazine article also hailed the Alligator as “revolutionary…the world’s first successful amphibious vehicle.”

Donald Roebling and his father John A. Roebling II were very happy with the national publicity and thought the years of hard work might now pay off. Little did they know that their first customers would be the United States Marine Corps.

Part 8. The “Alligator” at the Cocktail Party in San Diego

In retrospect, the series of events that happened next appear to happen on the ultra fine line that separates luck and destiny.

The same month the Life Magazine article appeared Rear Admiral Edwar Kalbfus, a Commander with the U.S. Fleet in San Diego, was at a cocktail party and happened to take a look at the new issue, and saw the article. Kalbfus showed the article to Major General Louis Little, Commander of the Fleet Marine Force. They were both excited about the amphibious vehicle.

In January 1938 Kalbfus mailed the article to Major General Thomas Holcomb, the Commander of the Marine Corps in Washington DC. (As Roan noted; In less than five years from January 1938 Roebling’s Alligator would be helping the US. Marines defeat the Japanese at Guadalcanal.)

Holcomb read about the Alligator and forwarded the article to the Marine Equipment Board in Quantico, Virginia.

Directing Brigadier General Frederick Bradman, President of the Equipment Board wanted Roebling’s vehicle evaluated so he could make a recommendation to the Marine Corps. As Roan pointed out, it was due to the zeal and advocacy of these high ranking officers that the Alligator was negotiated through the “labyrinth of military bureaucratic negativism and insufficient funding.”

In February of 1938 the Equipment Board sent a letter to Roebling requesting information. Roebling sent back a thorough package of information within five days. The Equipment Board was impressed.

Part 9. Rejection first, perseverance and acceptance later…

Two weeks later Major John Kaluf was sent to Clearwater. Kaluf’s trip to Clearwater to meet Roebling became a turning point in the Marine Corps attitude toward the Alligator.

Kaluf took 400 feet of 16mm film of Roebling’s amphibious vehicle in action and he personally drove the Alligator and observed it’s operational efficiency in the ocean, the surf, and on land. Kaluf was immediately convinced this was the essence of what the Marine Corps was striving to do, that is, project power from sea to land in a smooth transition.

Kaluf helped keep the Alligator’s prospects alive until it became a reality.

In June of 1938 the Commandant of the Marine Corps requested funds from the Chief of Naval Operations to purchase one Alligator for testing under military conditions.

But the news was not good. The Chief of Naval Operations did say the Alligator had the potential to provide some value to the Marine Corps, but limited funds were available and that availability would be used to continue development of the Navy’s landing boats.

Meanwhile, Donald Roebling continued to modify Model 4 of the Alligator, incorporating recommendations made during Kaluf’s Clearwater visit back in March of 1938. Roebling kept the Equipment Board up to date on his modifications.

Although the Navy for the time being had declined to fund the Alligator, in February of 1939 Kaluf went back to Clearwater in order to keep Roebling’s “enthusiasm and interest intact.”

During this trip, Roebling’s price tag of $18,000 generated sticker shock for Kaluf, but nevertheless Kaluf sent a report that remained as supportive as ever.

In that same report Kaluf also noted that Donald Roebling and his father were very wealthy people and seemed to be embarrassed when the issue of profit was addressed; The $18,000 was strictly based on covering production costs. Kaluf said the Roeblings could only be appealed to on the basis of patriotic or humanitarian motives when it came to the Alligator. Most of that $18,000 would initially come from Roebling’s pocket.

Later, in October of 1939 the Equipment Board had a new president who sent a three-man officer committee to Clearwater that subsequently gave a glowing report of the Alligator, and the Navy decided to relinquish funds to purchase one pilot vehicle. Congress eventually approved a $20,000 contract for the Navy Bureau of Ships to pay for the pilot vehicle.

Part 10. The First “Alligator” delivered and Roebling makes history

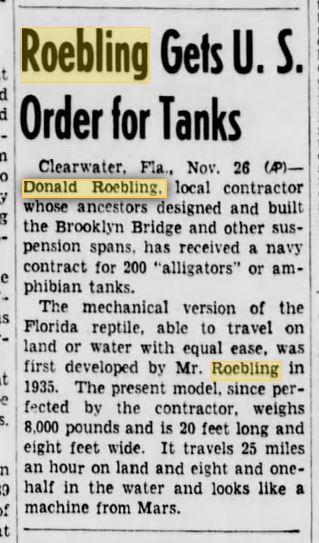

Brooklyn Daily Eagle news brief

about Donald Roebling’s contract

with the U.S. Navy that purchased

200 of Roebling’s amphibious “Alligator”.

The AP writer said the “Alligator”

“…looks like a machine from Mars.”

A year later in October of 1940 Roebling delivered the first Alligator to the Navy with the “military modifications” suggested during the earlier visits by Kaluf and Moses.

The 1940 Alligator had a 120 horsepower Lincoln Zephyer engine and clocked a speed of 29 mph on land and 9.72 mph in water. The cargo capacity was 7,000 pounds. The Marine Corps now had a true amphibian vehicle.

In 1941 the Alligator was sent to Culebra Island in the Caribbean for field testing. The Commander of the Atlantic Fleet was impressed and on February 1941 the Navy contracted Donald Roebling to build 200 alligators while the contract stipulated two major modifications.

The only modifications were that the aluminum would be replaced with welded steel plating for protection from small arms fire, and the Lincoln Zephyer engine would be replaced with a slower speed heavy duty 146 horsepower engine.

As Roan pointed out, the construction of 200 vehicles would be impossible to produce in Roebling’s machine shop where all the previous work had taken place.

Roebling momentarily disregarded that problem and signed the Navy’s $3,300,000 contract that required a delivery date of July 1941, which was just 5 months prior to the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor.

What Roebling did was subcontract production to the Food Machinery Corporation (FMC) that had a citrus processing machinery plant in nearby Dunedin. FMC had already built many of the individual parts for the Alligator.

Roebling and the President of FMC rapidly created a design and production team while a large number of welders and technicians were shipped in from other FMC plants around the country.

Sometimes the redesign of the military specifications was extremely challenging because, as mentioned earlier, Roebling disliked engineering plans and blueprints. Roebling had relied more on the real-time creative process from his small team while building the first prototypes.

As Roan noted, apparently the FMC team was inspired by the imminent threat of war in the Pacific, the huge war time production requirements, and of course, profits. The plant produced all 200 Alligators for the Navy and the Marine Corps by August of 1941, only one month after the initial contract deadline.

The official military designation for the Alligator was Landing Vehicle Track (1) LVT(1). The Marine Corps crewmen always called it just the “Alligator.” Although it wasn’t perfect and needed a lot of repairs during periods of operation, the Marine Corps officially considered the Alligator “a technological innovation that profoundly contributed to the wartime Marine Corp’s ability to conduct a truly amphibious projection of military power ashore, that seamless transition from water to land.”

This was a problem the Marine Corps had been trying to solve for a long time, that is, until John A. Roebling II and his “eccentric” son Donald went to work to solve rescue problems during the aftermath of Florida hurricanes.

The Alligator’s first real war time test was at Guadalcanal where it played a vital role in America’s victory against the Japanese in the Pacific.

Part 11. Roebling’s Eccentricities and Generous Philanthropy in Clearwater

During and after the period of time Roebling developed the Alligator, he also did many things in Clearwater that contributed to his reputation as an eccentric millionaire, and, in many cases, his reputation as a very generous behind-the-scenes philanthropist.

A great deal of the information in this section of the “Footprint” series is based on the personal remembrances of people who knew and worked with Roebling during his lifetime in Clearwater, as documented in the pamphlet The Spirit of Morton Plant: A Retrospective 1916-1991.[8]

Morton Plant was a small hospital founded in 1916, not far from his estate. Roebling became personally involved with the hospital’s growth, even helping with hands-on construction work related to renovations and expansions.

The hospital today owes a great deal of its success to Roebling’s financial and personal contributions during the 1930s and 40s. At his death in 1959 he left a $1 million Trust Fund for the hospital, and provided for a substantial follow-up gift from his wife when she passed away in 1977. To this day the Trust Fund retains an asset base that fluctuates between $1-$5 million.[8]

All the personal accounts of Roebling from those people who worked with him or knew him as an acquaintance point out that he was never interested in any personal recognition for his many formidable acts of generosity.[8]

Not only were institutions like the local hospital, the boy scouts, and military personnel in nearby Dunedin, Florida, the recipients of Roebling’s frequent generosity, but he also provided anonymous gifts to local individuals.

As one former hospital board member recounted in reference to Roebling’s generosity: “Charity drives mysteriously reached their goals, worthy indigent students went to college under the sponsorship of an unknown benefactor, and food baskets appeared on the doorsteps of the poor.”[8]

One story reveals that he gave away a $35,000 airplane simply because he got tired of it. (The rate of inflation puts that plane’s value at a little over $400,000 in our 2014 economy.)

There is also the story of the organist for a local Catholic church, the mother of one of his employees, who developed a serious arthritic condition and wasn’t able to practice during the week on the church organ. Apparently Roebling got word of the situation and not long after, the organist came home one day to find that a brand new organ had been anonymously delivered to her home. This, she eventually found out, was a gift from Roebling.[8]

Regarding his eccentricity; One story has it that he once wanted to get rid of a cabin cruiser, so on a whim he loaded it with dynamite, anchored it offshore in Clearwater Bay a safe distance from his estate lawn, and from the porch of his mansion he fired shots from a high powered rifle at the boat until it exploded.[8]

Roeblings philanthropy within the Clearwater community was extensive to say the least.

In the 1930s, during the Great Depression, when the People’s National Bank of Clearwater was in danger of running out of money, he solved the problem one afternoon in a rare display of showmanship by standing on a tabletop in the bank lobby, loudly announcing his “faith” in the bank, and proceeded to make a huge deposit that would keep the bank financially solvent.[8]

The Donald Roebling Society to this day continues to be the largest donor organization for the Morton Plant Mease Foundation. Roebling’s generosity was not the only a major factor in the hospital’s long term development, he also devoted a great deal of his own time and engineering expertise to the hospital throughout his life. He even sometimes went to the site to personally help with construction of a new building.

Part 12. John and Margaret Roebling and Highland County, Florida

Photo: https://www.floridastateparks.org/park/Highlands-Hammock.

John A. Roebling II (Donald’s father) never completed the mansion (mentioned above) that he envisioned for his wife Margaret on his 1,000 acre estate in Lake Placid, Florida.

Margaret Roebling died of tuberculosis in October of 1930. She was intensely interested in horticulture, and before she died she donated $50,000 in two installments to what became one of Florida’s first four official state parks, the Highland Hammock State Park, a 9,000 acre tract of land in Sebring, Florida.[5]

Her first contribution of $25,000 was provided so a group of people could purchase the land for what was originally envisioned to be a botanical garden. The second contribution of $25,000 was given on the contingency that the local community come up with just $5,000, to prove their commitment to the project. The community held up its end of the bargain.[5]

John A. Roebling II, also donated $300,000 to the park for construction costs as a way to carry on his wife’s wish to open the park to the public.

At the time the park was considered for National Park status but instead, in 1935 Highlands Hammock Park in Sebring, Florida, became one of the original four Florida State Parks. And the effort by Margaret Roebling along with her fellow citizens was thought to be one of the finest examples of early grass roots organizing of public support for a conservation project.[5]

The Archbold Botanical Center, in Venus, Florida, is also the result of the Roebling Family philanthropy. After his wife’s death in 1930, John A. Roebling lost interest in the Red Hill Estate in Sebring, even though he had already built six buildings on the estate that were intended to house the employees.

One of Donald Roebling’s close friends, Richard Archbold, an aviator and professional biologist, recognized that the 1,000 acre stretch of land would make a valuable habitat reserve for indigenous trees, plants, and wildlife.[4]

Archbold convinced Donald Roebling to speak to his father. Donald Roebling convinced his father to donate the 1,000 acres and the buildings so that Archbold could create what is now the Archbold Botanical Station.[4]

Conclusion and Acknowledgments

I would like to thank the following sources and websites for the information on the Roebling family in Florida. And I would like to especially thank Major General Richard Roan (and the United States Marine Corps) for the thorough chronology and detailed timeline presented in Roan’s fascinating historical book, Roebling’s Amphibian: The Origin of the Assault Amphibian, that I quoted from and paraphrased a great deal in order to present this for the Brooklyn Footprints in Florida Blog Series.

References, Websites and Pages

1. http://www.globalsecurity.org/military/library/report/1987/RRW.htm. Contains United States Marine Corps Major Richard Roan’s historical account of the origins of the assault amphibian vehicle titled “Roebling’s Amphibian The Origin Of The Assault Amphibian.”

2. http://www.museumoffloridahistory.com.

3. http://www.wikipedia.com

4. http://www.archbold-station.org/

5. https://www.floridastateparks.org/park/Highlands-Hammock

6. http://www.ibiblio.org/hyperwar/USMC/ref/Roebling/Roebling.html

7. http://www.sun-sentinel.com/sfl-1928-hurricane-story.html#page=1

8. http://www.srh.noaa.gov/mfl/?n=okeechobee

By Liz Doup, Staff Writer, Sun-Sentinel

Publications:

9. The Spirit of Morton Plant: A Retrospective 1919-1991.

10. History of the Dunedin Masonic Lounge No 192.

11. The Sun Sentinel

12. The Brooklyn Public Library’s Brooklyn Daily Eagle Archives

13. The Brooklyn Daily Eagle